Now that only four NFL teams aren’t biding their days with golf and baths in hot tubs full of champagne after a season that dragged on like a lawnmower, one story emerges from the pocket.

It’s a story that’s been pre-written on thousands of PC’s (and now, Mac’s) belonging to thousands of harried American sportswriters looking for a chance to get in a story ahead of time and wax poetic against time itself. It’s Brett Favre, old man tethered to the past, digging in against the future.

In a country especially obsessed with appeals to times gone by (see: Republican campaign platforms, revival of fundamentalist religion) — times characterized by iron-rich family values, work ethic and general dirtiness, times that really weren’t all that good — and generally afraid of the future, Favre represents one of the last bastions of a time gone by in football. His is a face and his is a game that would jive perfectly with those coarse-grain, jaggedly flowing films of football from the 1940s. Now, he’s in stark contrast to our present time of young, pretty boy quarterbacks, who give every indication they’re more obsessed with the idea of being a quarterback than they are of playing quarterback. Joey Harrington, Matt Leinart, Brady Quinn, Rex Grossman, JP Losman. The damn list goes, sadly, on.

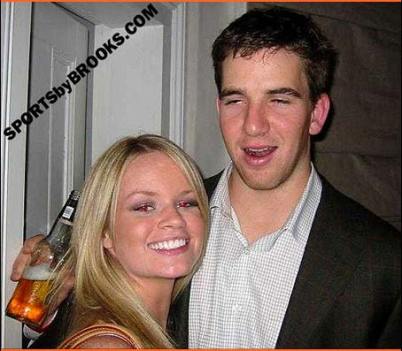

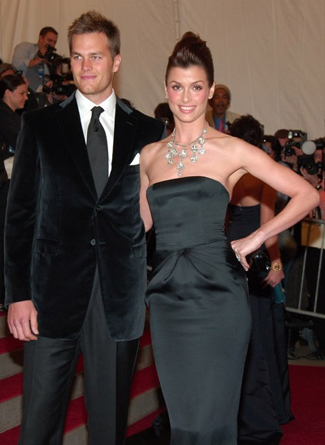

Of the quarterbacks who made it past the first round this year, Eli Manning whines constantly (and looks like he’s 15), Tony Romo border-hops with Jessica Simpson during playoff weeks, Phil Rivers taunts opposing quarterbacks. And although Tom Brady ain’t no real pretty boy, he does date Giselle Buendschen. Which, I guess, counts for something.

Prettyboy.

Prettierboy.

(ehhhh…)

Favre is the blast furnace to their iPhone. He’s the deep-dug dirt to their packets of Purell. He’s the sideburns and 5 o’clock shadow to their Maseratis, the achy joints and IcyHot to their trips to Cabo. Brett Favre (arguably deservingly) represents Main Street versus Park Avenue, gruff versus glamor, action versus words. Where you could see Eli Manning kicking back with a Smirnoff cocktail and pedicure, you could see Favre kicking back by mining coal.

And, as such, most of America now looks to Brett Favre to lead us backwards on the trail of time.

Every day, American life exists with an externally imposed and deeply uncomfortable mandate: the need to be perfect. It’s a subject I’ve touched on ad nauseum through this medium — the personal effects of voyeuristic and pushy media — but it’s one that’s so entrenched in culture that I feel like we forget about it sometimes.

Favre is so splendidly imperfect. He relies, like America did during its glorious post-WWII time, on brute force, his arms blasting shots like cannons built in Pittsburgh and Bethlehem, his legs burning like pistons churned out in Troy and Lansing and Gary.

Every time Favre jump-pirouettes out of 1,200 pounds of combined impending lineman, only to spin, shoot his eyes to the corner of their sockets and find someone sneaking into a fissure in the defense mid-stride, middle-aged men seem to all tacitly agree — we could do that.

I see him as having the appeal of a union leader. Much of this appeal stems from the loose and often-repeated half-truth that he looks like the rest of us, working as Wrangler jeans and GM truck spokesman. (Slate ran a great story about a month back dealing more or less with this buddy-like relationship between people and Favre) But, like a union leader, he stands above. He’s shown himself to be special, worthy of your adoration and reverence. He doesn’t need a podium — he’s got the huddle, the line of scrimmage, the HD cameras. Even off the field, he’s got this approached that has been described as workmanlike, down-to-business, terse. It’s not too much of a stretch to imagine him negotiating labor relations. All of these virtues make him as inspiring to the middle class as paychecks.

But really, all of the idolization derives from the fact that he plays the damn game like he’s about to burst. He plays the game like it was meant to be played, people say. There’s a whole lot of epistemological unpacking that could be done to that phrase, but it’s evocative nonetheless. Words like selflessness, teamwork, reckless abandon, sacrifice, courage and others that drag sports into the arena of life come to mind. But Favre seems to get all the good words.

The knock on the game now that rings out most collectively from our parents’ and grandparents’ generations is that it’s become more atomized — it’s about the players, not the game. My dad charges that it’s become a purer form of entertainment.

The argument requires some nuance, but Carl was up to the task: In olden times, the game itself was entertaining enough. People, my dad argues, were concerned with how the game was played and what the final score was — and only those things, apparently. I argued that the game has only changed for the better, due mainly to the fact that players today make guys in the 60s look slower than church. He said that wasn’t the point. The point is that the game has been pushed to the side of the stage, subservient to the individuals who play it.

Of course, even as early as the 60s — culminating in Broadway Joe Namath’s guarantee of a Jets win over crew-cut, straighter’n corn rows Johnny Unitas’ Colts in Super Bowl III — personalities have been the stories easiest to tell and most intriguing to listen to. Shakespeare didn’t write plots: he wrote people. Come to think of it, neither did Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld when they were writing Seinfeld. The best stories have always been about people clashing with people, not drones dragged through contrived plots.

Ultimately, Favre, by being such a gamer, has become as much a personality as anybody else. In essence, by fitting in so snugly into the model of what America holds a football player should be, he has indirectly made himself stand out. An atom all the same.

So, his aging frame now represents an America that exists in the sepia light of nostalgia. Times were never quite as good as they appear in memory, and the game of football was never quite as good as we’re made to believe it was. But Favre’s is a career that doesn’t need to be amplified. He’ll serve as a symbol over the next week and on, a relic left over from yore, and people will pull for him, because they’ll also be pulling for some hope for their own lives, for their country.

A number of components have conspired to whittle away at American confidence in the future, a pessimism that’s inspired two-thirds of people who performed an NBC/WSJ survey about the future to profess that they think their children’s lives will be worse than theirs. The modern economy’s co-opting of the American dream and emasculation of the self-made man mentality (huge corporations crush small businesses, medium crush smaller ones, etc.) hurt the Alger story/myth among the middle class (although entertainment, namely rap and sports, has granted the lower classes access to the myth).

Doubts about Social Security, our country’s credit rating and where America will stand in relation to the rest of the world economically and politically cloud the future, which was all Promised Land when we were growing up. Vietnam made us question our power across the globe. Iraq not only reinforced those questions, it has embarrassed us. Throw in the threats of terrorism and nuclear warfare and you’ve got some pre-mixed gloom.

Now, we don’t expect Brett Favre to solve the credit crisis and end the problems in Iraq. But for all intents and purposes, he serves now as a transitional item from a time when things were less uncertain, if not easier.

It’s unfair to saddle Favre with such a responsibility, but it’s the way things have been done for as long as history has told us they have. Nostalgia is an old term. Odysseus had nostalgia. And now, Favre is the golden past contrasted with the dark future.

My buddy Nick (who runs a more or less defunct blog at usss.wordpress.com that had a good run in late-summer) writes that he doesn’t like Favre for the following reasons:

“EVERY male announcer absolutely slurps him. During a broadcast, if he makes a poor throw, maybe too high, the call is always that the reciever couldn’t grab it. Seriously, every announcer LOVES him. It’s creepy, weird, and gets so annoying if you’re watching Green Bay on primetime. …

4) While every other athlete gets blasted for every trangression or mistake they make, everyone seems to excuse Brettski from his vicodin addiction that he only attened rehab for to avoid a $900,000 fine.

……………….and

..

..

..

5) Weren’t you rooting for Ben Stiller in “Something About Mary”?”

Leave a comment